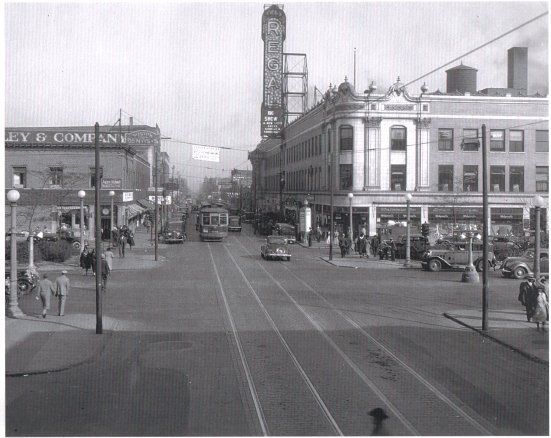

The Regal Theatre from 47th Street looking east across South Parkway (now King Drive).

The Regal Theatre from 47th Street looking east across South Parkway (now King Drive).

Over the decades since the demolition of Chicago's legendary Regal Theatre in 1973, one of the burning questions surfacing from time to time in the theatre organ world has been “What ever happened to the Regal Barton?” One of Dan Barton’s most prized instruments had seemingly fallen off the face of the earth. Well, now we know. The mystery has been solved, and we can now expect to once again thrill audiences with the sounds of this magnificent and unique instrument!

The story of Barton Organ #222 cannot be told without first shedding some light on the equally fascinating history of the Regal Theatre. Designed by Edward Eichenbaum of the firm Levy and Klein, and costing $1.5 Million to build, the Regal Theatre opened on February 4th, 1928 under the auspices of the Lubliner and Trinz chain. Levy and Klein, which had also produced the Diversey Theatre on the North Side, and the Marboro Theatre on the West Side, designed the Regal in the “atmospheric” style, with a blend of Moorish, Spanish and Far Eastern motifs. The 2,797-seat Regal eclipsed both of its predecessors in opulence and elegance. The ceiling of the auditorium was designed to look like a huge canopy supported on the side walls by massive gilded poles and offering peeks of a vaguely Middle-Eastern landscape between the poles. In the center of the polychrome canopy was a hole with a view of a deep blue sky with clouds and stars. The large proscenium arch was created to look like an Oriental temple, decked in gold, blue, and maroon. The Regal Theatre was also equipped with a state-of-the-art ventilation system, dressing rooms, an orchestra pit, and of course, the Barton organ.

Featuring live stage acts as well as movies, the theatre proved immensely popular, and quickly became not only a fixture in the black entertainment world, but a symbol of the African-American community in Chicago. Acts such as Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Ella Fitzgerald, The Temptations, Miles Davis, Nat “King” Cole, Duke Ellington, and many others were fixtures at the Regal. "Little" Stevie Wonder recorded his famous live version of the number-one hit single "Fingertips" at a Motown Revue there in June of 1962 that included Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, Mary Wells, and The Marvelettes. B.B. King recorded his famous Live at the Regal album there in November of 1964.

While it is thought that the Regal was the “Chicago version” of the famed Apollo Theatre in New York, it is very possible that the Regal actually INSPIRED the Apollo and the type of entertainment offered, given the fact that the Regal had been open for six years before the Apollo opened in 1934. After the abolition of slavery, and subsequently the Civil War, there was a great migration of former slaves to the North, and with it came the need for entertainment, as well as employment. The Regal Theatre was unusual for its hiring practices when it opened, as Lubliner and Trinz staffed its flagship palace with mostly African-American management, ushers, house musicians, cashiers and attendants. Most other major Chicago theatres at the time would only hire African-Americans for janitorial and behind-the-scenes jobs. The Regal, from its inception, was staffed almost entirely by blacks, up to and including its longest-tenured and most successful manager. The Regal served an important role in the community, offering opportunities that would have otherwise been quite inaccessible. Balaban and Katz had taken control of the Lubliner and Trinz theatre chain in the 1930’s, and recruited Fess Williams and his Royal Flush Orchestra as one of the house bands. The group had been one of the opening acts at the famed Savoy Ballroom, located on the same block as the Regal, and had gained quite a following. The Savoy and the Regal provided places for families to go in the city, which proved to be a very successful business model. Together, they made this stretch of South Parkway in Bronzeville popularly known as the “Harlem of Chicago” for its important cultural and social contribution to the African-American community in Chicago.

Business boomed for the first couple of years, but the Great Depression took its toll, and after B&K acquired the theatre, they had planned to close it. However, due to massive outcry by the city’s African-American community, they elected to leave the Regal open. By the late 1930’s the Regal was as popular as ever! Motion pictures and their immensely popular live stage shows continued right up until the theatre closed.

By the late 1960’s, it was apparent that the changing condition of the neighborhood and the need for the theatre’s refurbishment were making it impossible for operations to continue. The Regal Theatre closed in 1968, and in 1971, a suspicious fire damaged major portions of the building. The Regal Theatre was razed in 1973, and the lot remained vacant until the early 2000’s. Opening in 2004, the Harold Washington Cultural Center now occupies the place where the Regal Theatre once stood.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

The three-manual, 14-rank Regal Barton was known to be one of the “hottest” theatre organs in Chicago – and that was up against some pretty intense competition, even from its own builder! Barton, of course famous for organs installed at the Rialto Square Theatre in Joliet, Illinois, Hollywood Theatre in Detroit, Coronado Theatre in Rockford, Illinois, and in 1929, the largest unit organ ever constructed – the 6/51 job for Chicago Stadium – built some of the “snappiest” theatre organs around. The Regal was no exception. It was decided by Dan Barton himself that the area needed “a real jazz organ”, and as such, pipework scaling was larger, and overall wind pressures were higher than would be considered normal in an organ of that size. David Junchen is quoted in Volume One of his Encyclopedia of the American Theatre Organ as saying “…the Clarinet was the size of a small Diapason, and the Tibia trebles were as big as teacups…!”

Before the theatre closed, a group of interested individuals involved with CATOE (Chicago Area Theatre Organ Enthusiasts) including Dave Junchen, Jim Benzmiller, and Chris Feiereisen were determined to save the organ, so Benzmiller purchased it. Since it played fairly well up until the time the Regal shut its doors, and a final recording was made, with none other than longtime DTOS friend, the late, great Kay McAbee at the console.

When Jim Benzmiller purchased the Regal Barton, he reportedly planned to install it in a church. Those plans did not materialize, and it remained in the building until 1971, when the organ was sold to fellow CATOE members Harrison S. and Cathryn W. Baker of Chicago. After searching for a suitable home for the organ, the Bakers purchased the historic cream city brick Opera House in the small town of Amherst, Wisconsin, located in Portage County. Coincidentally, Amherst is the birthplace of Dan Barton himself! In 1971, the late Chris Feiereisen worked with the Bakers on the urgent task of removing the instrument from the Regal, and supervised its careful transfer to Amherst. Once the organ was saved from the wrecking ball, the Bakers intended to restore and install it in Amherst along with a small museum display, hoping to revive the historic Opera House and provide the community with a source of culture and entertainment.

Also in 1971, Harrison and Cathryn Baker met Dan Barton, then alert and in his 90’s. After visiting the Opera House, he wrote the Bakers that he looked forward to attending the first performance on the restored organ in Amherst. Over the years, Chris Feiereisen remained a friend to the Bakers, advising "Cassie" and Harrison as they undertook the patient labor of cleaning and re-leathering, which the two of them pursued over the years in the old Opera House building.

As a side note, Chris Feiereisen was a longtime member and friend of DTOS. Chris owned the 4/20 Wurlitzer Style Publix One from the Belmont Theatre in Chicago, and had installed it in a restaurant in Manitowoc, WI.

Dedicated, optimistic, and involved in many areas of interest throughout their lives, the Bakers were unable to realize their ambitious dreams for the Regal Barton. However, they never gave up on that dream. It is thanks to their providing safe storage for more than four decades that this irreplaceable pipe organ has survived.

Harrison Baker passed away on October 29, 2005 in Pennsylvania, after which Cathryn moved back to their home in Sheboygan. In early 2006, she asked Chris Feiereisen to re-examine the Regal Barton for her, and advise her of its condition. He found it to be remarkably intact, especially given its long storage, and at that time, an effort was launched to find an appropriate home for it. When she died on May 1, 2011, "Cassie" Baker still had not been able to place the Baker/Regal Barton into what she considered to be the right hands.

In late 2015, DTOS President John Cornue was put in touch with Anita Baker Al-Shaheen, a daughter of Harrison and Cathryn Baker, acting as trustee for her mother. Over the years, rumors had circulated in the pipe organ community regarding the condition of the organ. It had been reported that the organ was in deplorable condition, largely incomplete, covered in pigeon droppings, and presumably would never play again. Knowing that few people had seen the organ since it was taken to Amherst, and knowing that the only way to assess the condition of the organ would be to see it, John Cornue and Dean Rosko traveled to Amherst in October of 2015 to examine its condition personally. Mr. Cornue and the writer were in no way prepared for what we were about to see. Upon being guided into the Opera House, we noticed that much of the organ was not visible due to the fact that everything was covered in layers of protective cardboard. The console was at the front of the building, with nearly all of the other components scattered into just about every conceivable place. We ventured into the balcony, which had long been walled off from the rest of the building, and it became clear to us that some of the components which had been reported to be in poor condition were, in fact, not related to the Barton at all. Rather, they were parts of a Robert-Morton Tibia, and various other Wurlitzer-built components. Most of the metal pipes were located safe and dry in the basement of the Opera House, while the offset basses, wooden pipes, and everything related to the mechanism of the organ remained on the main floor. Most of the pipes were still stored in the packaging they were placed in when they came to the Opera House in 1971, never having been unwrapped. The vast majority of pipes were in better condition than what the writer has observed in many playing organs! The manual and offset windchests were all present, and in remarkably clean condition, as were the regulators, tremulants, “winkers”, and other components related to the winding system. The percussion instruments were in wonderful condition, some of them having been restored by the Bakers in Amherst. The organ was supplied with a ten-horsepower, large-shell Spencer Orgoblo, which was stored on the stage. It was found to be complete and in immaculate original condition. Overall, we estimate that the organ is at least 95% complete, and in good usable condition. It was determined that if we discovered anything missing, more than enough of the pipes were present to facilitate accurate replacement, and whatever may be damaged is certainly repairable. The console is easily the “roughest” part about the condition of the organ, but the pictures make it look worse than it is. Obviously, it needs a total restoration, with the stop tablets having been removed, and the keyboards rather beat up. However, the shell is complete and very solid. All of this is very doable, and is within the scope of the expertise and ability of DTOS and its members. We made the determination that day that there is no reason this historic, unique, and special instrument could not or should not play again. DTOS and its members not only appreciate this instrument’s significance, but also possess the technical capability to realize the Bakers' long-delayed dream right here in Wisconsin, as they intended.

DTOS promptly submitted an offer to purchase the Baker/Regal Barton. For various reasons, negotiations lapsed. For a time, all seemed lost. However, after re-establishing contact, in July of 2016, DTOS placed a fresh bid to purchase the Baker/Regal Barton, pending confirmation that the instrument remained in the same condition as we had observed at the Opera House the previous October. This was found to the be the case, and the trustees of the Cathryn W. Baker estate awarded the organ to DTOS. In October of 2016, almost a year to the date of our first visit, arrangements were made to bring it out of Amherst. On October 17th, members Greg Simanski, Jane Syme, Phil Becker, Rich Rosko, and Dean Rosko met in Amherst to begin removal. Armed with a 17’ U-Haul truck, we loaded as many parts as we could fit and brought them back to storage.

The following Friday, the DTOS crew, this time consisting of Zach Frame, Neill Frame, Ryan Jonas, John Cornue, Ryan Mueller, Greg Simanski, Phil Becker, Rich Rosko, Dean Rosko, and brother Aaron Rosko (who picked a “doozie” of an organ move to be his first!), loaded the rest of the organ onto a 26’ Ryder truck, and a 26’ U-Haul moving van. In addition to the two large trucks, the bed of Zach Frame’s pickup truck was full to the brim with swell shades, and various other components were stuffed into the beds of Greg Simanski and Phil Becker’s pickup trucks! With everything loaded, we headed south. Robin Gollnick met us at the storage facility on both Monday and Friday and was a great help getting everything unloaded. Gee…all of this sounds relatively simple on paper! All told, for the writer and others, that Friday added up to a 23-hour day, but one of the most rewarding there could possibly be!

When I, the writer, was involved in the rescue of the 5/74 Austin organ formerly housed in Chicago’s Medinah Temple, I often thought to myself that over the course of one’s life, one would surely only be afforded a single opportunity to save such an historic and unique piece of American musical history. A living, breathing piece of art. I consider DTOS very fortunate to have the opportunity to be involved in such a unique undertaking, and I could not have imagined that personally, I would have the chance to be involved in something so special. I liken the resurrection of this organ to bringing back Chicago Stadium Barton back to life, that is, if it still existed as a whole. I am profoundly humbled, and deeply honored.

Dan Barton was an entertainer by nature. The newsletter of this organization bears his name, and now, DTOS has a responsibility to the spirit, the memory, the legacy, and what has become the legend of this organ’s colorful creator to preserve it. This organ was intended to entertain the public, and DTOS will make sure that purpose is fulfilled. Barton was once the single most represented builder of theatre pipe organs in Milwaukee, and today, not a single one remains. DTOS is about to change that.

In that vein, we are exploring several options for the future of the Baker/Regal Theatre Barton. It is up to us to find the most suitable place, and as a definite location for the organ needs to be determined before any sort of major fundraising campaign can be launched, this is a high priority for us. We will keep you updated as the situation develops!

Text by Dean Rosko, with much assistance from Anita Baker Al-Shaheen.

The story of Barton Organ #222 cannot be told without first shedding some light on the equally fascinating history of the Regal Theatre. Designed by Edward Eichenbaum of the firm Levy and Klein, and costing $1.5 Million to build, the Regal Theatre opened on February 4th, 1928 under the auspices of the Lubliner and Trinz chain. Levy and Klein, which had also produced the Diversey Theatre on the North Side, and the Marboro Theatre on the West Side, designed the Regal in the “atmospheric” style, with a blend of Moorish, Spanish and Far Eastern motifs. The 2,797-seat Regal eclipsed both of its predecessors in opulence and elegance. The ceiling of the auditorium was designed to look like a huge canopy supported on the side walls by massive gilded poles and offering peeks of a vaguely Middle-Eastern landscape between the poles. In the center of the polychrome canopy was a hole with a view of a deep blue sky with clouds and stars. The large proscenium arch was created to look like an Oriental temple, decked in gold, blue, and maroon. The Regal Theatre was also equipped with a state-of-the-art ventilation system, dressing rooms, an orchestra pit, and of course, the Barton organ.

Featuring live stage acts as well as movies, the theatre proved immensely popular, and quickly became not only a fixture in the black entertainment world, but a symbol of the African-American community in Chicago. Acts such as Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Ella Fitzgerald, The Temptations, Miles Davis, Nat “King” Cole, Duke Ellington, and many others were fixtures at the Regal. "Little" Stevie Wonder recorded his famous live version of the number-one hit single "Fingertips" at a Motown Revue there in June of 1962 that included Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, Mary Wells, and The Marvelettes. B.B. King recorded his famous Live at the Regal album there in November of 1964.

While it is thought that the Regal was the “Chicago version” of the famed Apollo Theatre in New York, it is very possible that the Regal actually INSPIRED the Apollo and the type of entertainment offered, given the fact that the Regal had been open for six years before the Apollo opened in 1934. After the abolition of slavery, and subsequently the Civil War, there was a great migration of former slaves to the North, and with it came the need for entertainment, as well as employment. The Regal Theatre was unusual for its hiring practices when it opened, as Lubliner and Trinz staffed its flagship palace with mostly African-American management, ushers, house musicians, cashiers and attendants. Most other major Chicago theatres at the time would only hire African-Americans for janitorial and behind-the-scenes jobs. The Regal, from its inception, was staffed almost entirely by blacks, up to and including its longest-tenured and most successful manager. The Regal served an important role in the community, offering opportunities that would have otherwise been quite inaccessible. Balaban and Katz had taken control of the Lubliner and Trinz theatre chain in the 1930’s, and recruited Fess Williams and his Royal Flush Orchestra as one of the house bands. The group had been one of the opening acts at the famed Savoy Ballroom, located on the same block as the Regal, and had gained quite a following. The Savoy and the Regal provided places for families to go in the city, which proved to be a very successful business model. Together, they made this stretch of South Parkway in Bronzeville popularly known as the “Harlem of Chicago” for its important cultural and social contribution to the African-American community in Chicago.

Business boomed for the first couple of years, but the Great Depression took its toll, and after B&K acquired the theatre, they had planned to close it. However, due to massive outcry by the city’s African-American community, they elected to leave the Regal open. By the late 1930’s the Regal was as popular as ever! Motion pictures and their immensely popular live stage shows continued right up until the theatre closed.

By the late 1960’s, it was apparent that the changing condition of the neighborhood and the need for the theatre’s refurbishment were making it impossible for operations to continue. The Regal Theatre closed in 1968, and in 1971, a suspicious fire damaged major portions of the building. The Regal Theatre was razed in 1973, and the lot remained vacant until the early 2000’s. Opening in 2004, the Harold Washington Cultural Center now occupies the place where the Regal Theatre once stood.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

The three-manual, 14-rank Regal Barton was known to be one of the “hottest” theatre organs in Chicago – and that was up against some pretty intense competition, even from its own builder! Barton, of course famous for organs installed at the Rialto Square Theatre in Joliet, Illinois, Hollywood Theatre in Detroit, Coronado Theatre in Rockford, Illinois, and in 1929, the largest unit organ ever constructed – the 6/51 job for Chicago Stadium – built some of the “snappiest” theatre organs around. The Regal was no exception. It was decided by Dan Barton himself that the area needed “a real jazz organ”, and as such, pipework scaling was larger, and overall wind pressures were higher than would be considered normal in an organ of that size. David Junchen is quoted in Volume One of his Encyclopedia of the American Theatre Organ as saying “…the Clarinet was the size of a small Diapason, and the Tibia trebles were as big as teacups…!”

Before the theatre closed, a group of interested individuals involved with CATOE (Chicago Area Theatre Organ Enthusiasts) including Dave Junchen, Jim Benzmiller, and Chris Feiereisen were determined to save the organ, so Benzmiller purchased it. Since it played fairly well up until the time the Regal shut its doors, and a final recording was made, with none other than longtime DTOS friend, the late, great Kay McAbee at the console.

When Jim Benzmiller purchased the Regal Barton, he reportedly planned to install it in a church. Those plans did not materialize, and it remained in the building until 1971, when the organ was sold to fellow CATOE members Harrison S. and Cathryn W. Baker of Chicago. After searching for a suitable home for the organ, the Bakers purchased the historic cream city brick Opera House in the small town of Amherst, Wisconsin, located in Portage County. Coincidentally, Amherst is the birthplace of Dan Barton himself! In 1971, the late Chris Feiereisen worked with the Bakers on the urgent task of removing the instrument from the Regal, and supervised its careful transfer to Amherst. Once the organ was saved from the wrecking ball, the Bakers intended to restore and install it in Amherst along with a small museum display, hoping to revive the historic Opera House and provide the community with a source of culture and entertainment.

Also in 1971, Harrison and Cathryn Baker met Dan Barton, then alert and in his 90’s. After visiting the Opera House, he wrote the Bakers that he looked forward to attending the first performance on the restored organ in Amherst. Over the years, Chris Feiereisen remained a friend to the Bakers, advising "Cassie" and Harrison as they undertook the patient labor of cleaning and re-leathering, which the two of them pursued over the years in the old Opera House building.

As a side note, Chris Feiereisen was a longtime member and friend of DTOS. Chris owned the 4/20 Wurlitzer Style Publix One from the Belmont Theatre in Chicago, and had installed it in a restaurant in Manitowoc, WI.

Dedicated, optimistic, and involved in many areas of interest throughout their lives, the Bakers were unable to realize their ambitious dreams for the Regal Barton. However, they never gave up on that dream. It is thanks to their providing safe storage for more than four decades that this irreplaceable pipe organ has survived.

Harrison Baker passed away on October 29, 2005 in Pennsylvania, after which Cathryn moved back to their home in Sheboygan. In early 2006, she asked Chris Feiereisen to re-examine the Regal Barton for her, and advise her of its condition. He found it to be remarkably intact, especially given its long storage, and at that time, an effort was launched to find an appropriate home for it. When she died on May 1, 2011, "Cassie" Baker still had not been able to place the Baker/Regal Barton into what she considered to be the right hands.

In late 2015, DTOS President John Cornue was put in touch with Anita Baker Al-Shaheen, a daughter of Harrison and Cathryn Baker, acting as trustee for her mother. Over the years, rumors had circulated in the pipe organ community regarding the condition of the organ. It had been reported that the organ was in deplorable condition, largely incomplete, covered in pigeon droppings, and presumably would never play again. Knowing that few people had seen the organ since it was taken to Amherst, and knowing that the only way to assess the condition of the organ would be to see it, John Cornue and Dean Rosko traveled to Amherst in October of 2015 to examine its condition personally. Mr. Cornue and the writer were in no way prepared for what we were about to see. Upon being guided into the Opera House, we noticed that much of the organ was not visible due to the fact that everything was covered in layers of protective cardboard. The console was at the front of the building, with nearly all of the other components scattered into just about every conceivable place. We ventured into the balcony, which had long been walled off from the rest of the building, and it became clear to us that some of the components which had been reported to be in poor condition were, in fact, not related to the Barton at all. Rather, they were parts of a Robert-Morton Tibia, and various other Wurlitzer-built components. Most of the metal pipes were located safe and dry in the basement of the Opera House, while the offset basses, wooden pipes, and everything related to the mechanism of the organ remained on the main floor. Most of the pipes were still stored in the packaging they were placed in when they came to the Opera House in 1971, never having been unwrapped. The vast majority of pipes were in better condition than what the writer has observed in many playing organs! The manual and offset windchests were all present, and in remarkably clean condition, as were the regulators, tremulants, “winkers”, and other components related to the winding system. The percussion instruments were in wonderful condition, some of them having been restored by the Bakers in Amherst. The organ was supplied with a ten-horsepower, large-shell Spencer Orgoblo, which was stored on the stage. It was found to be complete and in immaculate original condition. Overall, we estimate that the organ is at least 95% complete, and in good usable condition. It was determined that if we discovered anything missing, more than enough of the pipes were present to facilitate accurate replacement, and whatever may be damaged is certainly repairable. The console is easily the “roughest” part about the condition of the organ, but the pictures make it look worse than it is. Obviously, it needs a total restoration, with the stop tablets having been removed, and the keyboards rather beat up. However, the shell is complete and very solid. All of this is very doable, and is within the scope of the expertise and ability of DTOS and its members. We made the determination that day that there is no reason this historic, unique, and special instrument could not or should not play again. DTOS and its members not only appreciate this instrument’s significance, but also possess the technical capability to realize the Bakers' long-delayed dream right here in Wisconsin, as they intended.

DTOS promptly submitted an offer to purchase the Baker/Regal Barton. For various reasons, negotiations lapsed. For a time, all seemed lost. However, after re-establishing contact, in July of 2016, DTOS placed a fresh bid to purchase the Baker/Regal Barton, pending confirmation that the instrument remained in the same condition as we had observed at the Opera House the previous October. This was found to the be the case, and the trustees of the Cathryn W. Baker estate awarded the organ to DTOS. In October of 2016, almost a year to the date of our first visit, arrangements were made to bring it out of Amherst. On October 17th, members Greg Simanski, Jane Syme, Phil Becker, Rich Rosko, and Dean Rosko met in Amherst to begin removal. Armed with a 17’ U-Haul truck, we loaded as many parts as we could fit and brought them back to storage.

The following Friday, the DTOS crew, this time consisting of Zach Frame, Neill Frame, Ryan Jonas, John Cornue, Ryan Mueller, Greg Simanski, Phil Becker, Rich Rosko, Dean Rosko, and brother Aaron Rosko (who picked a “doozie” of an organ move to be his first!), loaded the rest of the organ onto a 26’ Ryder truck, and a 26’ U-Haul moving van. In addition to the two large trucks, the bed of Zach Frame’s pickup truck was full to the brim with swell shades, and various other components were stuffed into the beds of Greg Simanski and Phil Becker’s pickup trucks! With everything loaded, we headed south. Robin Gollnick met us at the storage facility on both Monday and Friday and was a great help getting everything unloaded. Gee…all of this sounds relatively simple on paper! All told, for the writer and others, that Friday added up to a 23-hour day, but one of the most rewarding there could possibly be!

When I, the writer, was involved in the rescue of the 5/74 Austin organ formerly housed in Chicago’s Medinah Temple, I often thought to myself that over the course of one’s life, one would surely only be afforded a single opportunity to save such an historic and unique piece of American musical history. A living, breathing piece of art. I consider DTOS very fortunate to have the opportunity to be involved in such a unique undertaking, and I could not have imagined that personally, I would have the chance to be involved in something so special. I liken the resurrection of this organ to bringing back Chicago Stadium Barton back to life, that is, if it still existed as a whole. I am profoundly humbled, and deeply honored.

Dan Barton was an entertainer by nature. The newsletter of this organization bears his name, and now, DTOS has a responsibility to the spirit, the memory, the legacy, and what has become the legend of this organ’s colorful creator to preserve it. This organ was intended to entertain the public, and DTOS will make sure that purpose is fulfilled. Barton was once the single most represented builder of theatre pipe organs in Milwaukee, and today, not a single one remains. DTOS is about to change that.

In that vein, we are exploring several options for the future of the Baker/Regal Theatre Barton. It is up to us to find the most suitable place, and as a definite location for the organ needs to be determined before any sort of major fundraising campaign can be launched, this is a high priority for us. We will keep you updated as the situation develops!

Text by Dean Rosko, with much assistance from Anita Baker Al-Shaheen.